I assumed British domestic pets were safe with families during World War 2. Of course, the bombings and food shortages were threats. If pets found themselves alone, how would they survive? Back then, there wasn’t the microchip that we had today. But bombs dropping, food shortages and becoming a stray were the least of domestic pet problems. The stark reality was the pet cull during World War 2.

During the Second World War, The National ARP Animal Committee (NARPAC) started the Animal Guardians to register found animals to reunite with their owners later. When I started reading about lost pets during the Second World War, I stumbled upon a topic I never knew, making me cry.

A mass hysteria occurred following a 1939 BBC broadcast about the contents of a printed notice from the NARPAC and the Home Office. It resulted in a holocaust of British family pets between 1939 and 1940.

It is estimated that 750,000 pets were destroyed. More alarmingly, national welfare charities destroyed these animals and the charities we know today. It is a history they would rather forget.

The four charities involved were:

- Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA)

- People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals (PDSA)

- National Canine Defence League (Dog’s Trust)

- Battersea Dogs and Cats Home

Helping animals during manmade or natural disasters

Today we have various organisations and individuals that, during man-made or natural disasters, offer a professional and managed response to help animals in need. An example is the RSPCA’s Animal Rescue Team.

Organizations and individuals include:

- Veterinary staff

- Volunteers

- Animal welfare officers

- Animal rescue staff

- Emergency medical service personnel

- Firefighters

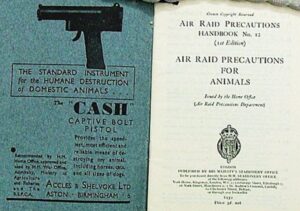

In contrast, back in the summer of 1939, the Home Office published advice only about how to look after your animals during an air raid. The name of the pamphlet was: ARP Handbook No. 12 – Air Raid Precautions for Animals.

‘When an owner has been unable to send his dog or cat to a safe area, he should consider the advisability of having it painlessly destroyed. During an emergency, there might be large numbers of animals wounded, gassed or driven frantic with fear, and destruction would then have to be enforced by the responsible authority for the protection of the public.’

The National Air Raid Precautions Animal Committee published their own notice called Advice to Animal Owners. The publication caused catastrophic consequences.

“If at all possible, send or take your household animals into the country in advance of an emergency.” It concluded: “If you cannot place them in the care of neighbours, it really is kindest to have them destroyed.”

A mass hysteria happened, and a total of 750,000 British pets were either killed by owners or destroyed by charities. This figure includes the massacre of 400,000 pets during one week in 1939.

There was a combination of fear from animal owners.

- Evacuation

- Animals were barred from air-raid shelters

- Food rationing.

- Food for animals was not considered.

The Home Office and the NARPAC were not to abandon animals or dump them on the street.

The main reasons for this were:

- Aggression from starving dogs and a danger to the public

- Sirens would cause animals to act in a frenzied manner

- Biological contamination spread

- Gas

- In general, cats and dogs going wild

So the suggestion was the kindest thing was to have a pet euthanized if the owner could not evacuate to the countryside with their pet. But the public misunderstood, and people queued to have their pets killed.

The British domestic pet cull became known as the pet holocaust.

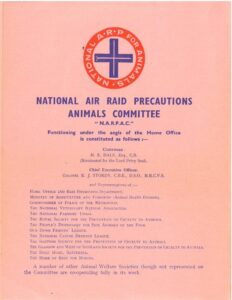

Who is NARPAC? (National ARP Animal Committee)

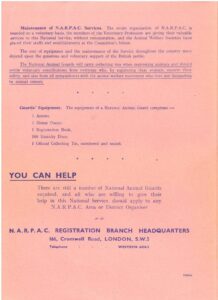

The foundation advised owners on animals, working animals and farm animals, and worked alongside veterinarians, the police, animal welfare and other local authorities. It aimed to help animals.

The other aim was to get animals registered. This was an early ‘microchip’. A cat, for example, wore an identity collar with a number reference.

If animals and owners were separated during air raids, the identity collar helped both be reunited. From what I have read, the scheme devised was set up with all good intentions. It was not about rescuing or rehoming in the beginning, if at all. It was about compiling records of animals and first aid for pets injured in the bombings.

In 1945, the NARPAC closed, and any assets went to the PDSA. There were issues between NARPAC and the charities about procedures.

The reality of the cull of British domestic pets

Image from The Independent

The first cull began late summer 1939, and the second in September 1940.

But the unintentional dark side of the NARPAC began with the publishing of Advice to Animal Owners. But as shown in the history books and the figures above, it backfired. Instead of a large percentage of family pets being sent to safety in the countryside, queues of owners lined outside clinics to hand over their moggies or pedigree cats or dogs for destruction. Owners thought it compulsory, from what I understand.

Another reality was the potential increase in strays after bombings. Or pets being left behind when owners were evacuated. Several owners locked their pets up in houses – this, therefore, led to a torturous death of starvation and dehydration.

The experienced stray cat seemed to fare better than its domesticated counterpart. They were perfect for killing machines for rats and mice. And by all measures, were exempted from the cull. The stray would have been used to the harsh dangers of noise and weather too.

A proportion of French cats even hitched a ride from Dunkirk in the 1940s, which brought more moggies to the British shores. This led to a compulsory order of cats in coastal towns being destroyed.

The Times tried to stop the mass hysteria of pet culling

The Times published a comment to appease the original advice that created the hysteria.

‘A widespread and persistent rumour that it is now compulsory to get rid of domestic animals is causing many thousands to be taken for destruction. Centres run by animal welfare societies are filled with the bodies of animals. The National ARP Animals Committee emphasises that there is no truth in this rumour.’

The Times – 7th September

Some pet owners made their own air raid shelters where they could take their pets. Others surrendered pets because of food rationing or being enlisted. Owners queuing outside clinics included, surprisingly, the wealthy too.

War meant a lack of food – families had to be fed, which meant nothing for their pets. Living in the 21st Century, where everything is available 24/7, even during Covid-19, it is hard to believe a pet could be euthanized if an owner cannot provide food for its pet or out of concern their pet may not survive life as a stray if the home is bombed. But here we are in November 2022; pet owners are surrendering their pets to rescue centres or making an appointment with the vet for euthanasia because money is needed to feed families and provide heating.

Surprisingly, notices began appearing in the press, so I would like to add a quote from the BBC News in an article called The Little-Told Story of the Massive World War 2 Pet Cull:

‘ “Happy memories of Iola, sweet, faithful friend, given sleep September 4th 1939, to be saved suffering during the war. A short but happy life – 2 years, 12 weeks. Forgive us, little pal,” said one in Tail-Wagger Magazine.’

Tail – Wagger Magazine

How many pets did our British animal charities euthanize?

Charities we know and love today have a dark secret and played an initial part in the pet culling.

The war was a different era. Sources and provisions, and knowledge were far less superior than today. We know that the government’s pamphlet and NARPAC advice caused panic among pet owners. And there was fear and reality of war. Husbands, sons, and nephews going to fight, lack of food and the threat of the home being bombed. Pet owners believed killing their pets or having them euthanized was compulsory, an essential part of war life. Wealthy families readily surrendered their pets too.

A book called Please Take Me Home – The Story of the Rescue Cat, by Clare and Christy Campbell, is an interesting read as covers information about the rescue cat from 1850. It is available as a hardback, paperback and Kindle.

The charities we know today were under the umbrella of the NARPAC, and before the start of the massacre, each had to submit information about their mass pet destruction capabilities. In the late thirties and early forties, charities that were there to help animals became their executioner.

The volume of pets destroyed:

- PDSA destroyed 300,000 London pets in a matter of days

- National Canine Defence League (now Dog’s Trust) and Our Dumb Friends’ League offered assistance

- The RSPCA had 52 cats and dog lethally centres in London

- Battersea had high-voltage electrothonators. Although I read elsewhere that Battersea was against destroying animals and subsequently fed and cared for 145,000 dogs alone

I cannot imagine anything more heartbreaking.

British pets were slaughtered by barbaric methods during the war. – and as mentioned before,

The identity collar (‘microchip’) and the National Animal Guards

The NARPAC’s recruited Animal Guards stationed in different locations, initially raising to 47,000 volunteers; eventually, this number decreased by half because of squabbles.

The Imperial War Museum has the early cat identification collar on display. The collar consisted of white elastic with a suspension ring, a metal engraved disc showing a red cross, and a single inscription: NARPAC Registration of Animals.

Identification specification.

Disc:

Width 24mm

Height 31mm

Depth 1mm

Disc and collar:

170mm height

The identity collar belonged to a cat called Bobby.

- Cat

- Smoke grey tabby

- Half Persian (half tail)

- Neutered

- Expiry date 21 July 1945

Volunteers recorded each cat and included a name and address on a register to hopefully reunite it with its owner one day. Each disc had a number. The Guardian wore uniforms to identify themselves – armbands, helmets with the NARPAC logo and bicycle badge, and cycled the streets with nets and baskets to capture cats. Eventually, they had transport which they were allowed to use during air raids.

1940 was the final massacre, and animals were saved

In September 1940, the pet massacre began again, and another 10,100 pets were destroyed. Eventually, because of differences, the charities started withdrawing support from the NARPAC.

The RSPCA began searching for animals buried in bomb sites, carrying first aid and offering temporary refuge and food before being rehomed. So that same month, they helped 5,490 cats.

Our Dumb Friends League asked the public across Great Britain to take in any stray cats, and they would collect them. Volunteer groups were set up to shelter stray animals found amongst the debris until the charity could collect them. The animal welfare charity pleaded with cat owners to tell them in writing if evacuating their homes and leaving their cats locked up left their feline locked up inside. Other owners released their animals onto the streets to fend for themselves.

“Homes in the country urgently required for those dogs and cats which must otherwise be left behind to starve to death or be shot.”

Duchess of Hamilton and her statement with the BBC

Staff from her St John’s Wood home helped rescue many animals and Ferne Sanctuary, originally a heated aerodrome at her Wiltshire estate, became a safe place for pets.

Offers came from rural homes to help evacuee pets and private transport to take animals from their plight to safe refuge.

The RSPCA asked for homes for animals via a Want Register and in 1940, managed to rehome 91 animals.

According to the Forces War Records, the Royal Army Veterinary Corps wanted dogs for the war effort, so the RSPCA tried to stop the cull of dogs so they could be used during the war.

Pet saviours also grabbed pets from owners’ arms as they stood in line at destruction clinics. Those were the lucky ones but 750,000 innocent British pets were not. And when we see the purple poppy as a remembrance to animals who lost their lives in battle, please remember those 750,00 pets who lost their life too.

Many stories, facts, and horrors are untold or published, and the cull of World War 2 is a heartbreaking read for today’s animal lover. Again, I recommend reading the book Please Take Me Home – The Story of the Rescue Cat as it contains interesting facts about the cat, and you can buy it from Amazon. If The Works shop is local to you, have a look to see if the book is for sale there too.

Related articles:

- Real-life dogs dedicated to their owners

- Adopting an overseas rescue dog

- Real-life missing dogs and cats

- Working with the RSPCA

- Transfer to a microchip company that offers a free address update and lost & found service

Written in memory of 750,000 domestic pets

All I can write is – sending my love, and as a human, knowing those faithful pets depended on us, but we let you down.